To be a brown man in a white game

"How many more times will I have to protect you?"

Usman Khawaja said it partly in jest but with exasperation when we met after nets in Perth, four days from the first Ashes Test. It was the team’s first full training session of the summer.

I was watching from my usual spot above the nets—a spot I’ve used since Test cricket began at Perth’s Optus Stadium seven years ago. Yet a security guard approached and rudely told me to leave. He doubled down when I stood my ground. Khawaja, as he has done for me across the country over the years, stepped in and told him to "leave me alone." The guard even returned briefly with clear ill intent after another player joked he should "get rid of me."

This was a first in Perth. Elsewhere, especially at the Gabba, it’s almost routine. Even Marnus Labuschagne and Steve Smith have stopped batting to support me at times. At least I don’t get ganged up on anymore—usually it’s just one person who doesn’t like my look. I’ve sometimes called Cricket Australia officials beforehand, particularly before a Brisbane Test, but it’s not on them. There’s always someone.

So when Khawaja pointed at me and mentioned bailing me out from recurring harassment, it mattered. He brought it up mid-answer about being racially profiled throughout his long career. It was that moment in his 52-minute retirement press conference when he realized everything he’d said about his experiences would be dismissed by many as a "brown guy playing the race card."

He wasn’t. And it made sense to highlight our shared reality as the two coloured men in the room.

This isn’t about me. It’s about Khawaja, and why I related to the 39-year-old choosing to air uncomfortable views on a day many wanted him to "stick to cricket." You don’t always plan it. From experience, it’s never comfortable to raise discrimination—to be that guy, to spotlight what others find confronting. It’s the same for a high-profile athlete discussing politics or religious intolerance instead of "sticking to their lane."

I met Uzzy an hour after his press conference. We agreed he made the right call speaking from the heart, spilling his feelings in one go. This was likely his last media chat as a current Test cricketer.

The fair way to handle the non-cricket issues he raised is to at least acknowledge his perspective, not dismiss it unilaterally—as if his views count for nothing.

Khawaja spoke about being regularly "gaslit" when he talks of being a brown man in a largely white world.

That’s often what hurts most: being repeatedly told you’re wrong, that you’re imagining the vilification or bias, that as a migrant you should just be grateful for the opportunities this country gave you. As if pledging allegiance to Australia means losing the right to call out abuse, even when you’re the target.

That gratitude should be unconditional—even if you always add, "I love Australia and what it’s given me," whenever you describe how some treat you.

I fiercely defend Australia when anyone overseas, especially from the subcontinent, calls the whole country "racist." Khawaja does the same when discussing his role in bringing people together. It’s fair to say Australia is still a young country; true inclusivity will take generations.

But the last 24 hours have shown how long that might take. The hate and vitriol Khawaja faced for sharing his experiences has been awful—but expected. That’s just how it is.

Social media is vile. Putting yourself out there invites hate. But being relentlessly called a "grifter," "bed-wetting sook," "shit skin," "poojeet," or "radio DEI prick"—I’m almost impressed by the creativity of the insults—wears you down. So does being told to kill yourself, or hearing how many are waiting for you to commit suicide, as I have since yesterday.

It adds up. The cumulative impact manifests in an unhinged narration of your reality as a coloured person in an adopted land—like with Khawaja in his presser, and with me here.

You start trying to fit in, as Khawaja said he did. But you realize you never will. Enough people remind you you’re an outsider. Eventually, it’s about being accepted for who you are. Some, like Uzzy and I, get a platform and voice. Most don’t. That’s why it’s imperative we speak.

But trying to encapsulate 15 years in the spotlight looking different, and 30 years growing up routinely made to feel unwelcome, in under an hour—it’s human for voices and issues to get conflated.

It’s also natural for some in media and elsewhere to feel singled out by what Khawaja said. Good people who never treated him differently. Mainstream print media has been fair to him this summer—reporting facts, noting his significant drop in form as an opener after being the world’s best, mentioning his golf before Perth. What others made of those reports is beyond their control.

But as I’ve found writing on these issues, thoughts arrive as a chunk of emotion, not isolated rational opinions. So cut him slack if you think he intentionally offended anyone.

You question it constantly. Is it all in your mind? Does that colleague in the media centre look at you with disgust, avert their eyes when you greet them? Maybe they just don’t rate you professionally.

But you see it in their eyes. You’ve seen that look in airports, on streets, at supermarkets. You recognize it, but now it’s in your safe space: the cricket world.

Do you bring it up? Let it slide? But for how long?

You hint at it to others, who usually sympathize. They put an arm around you but then say, fairly and politely, "It’s unfortunate, but I won’t know what that lived experience feels like."

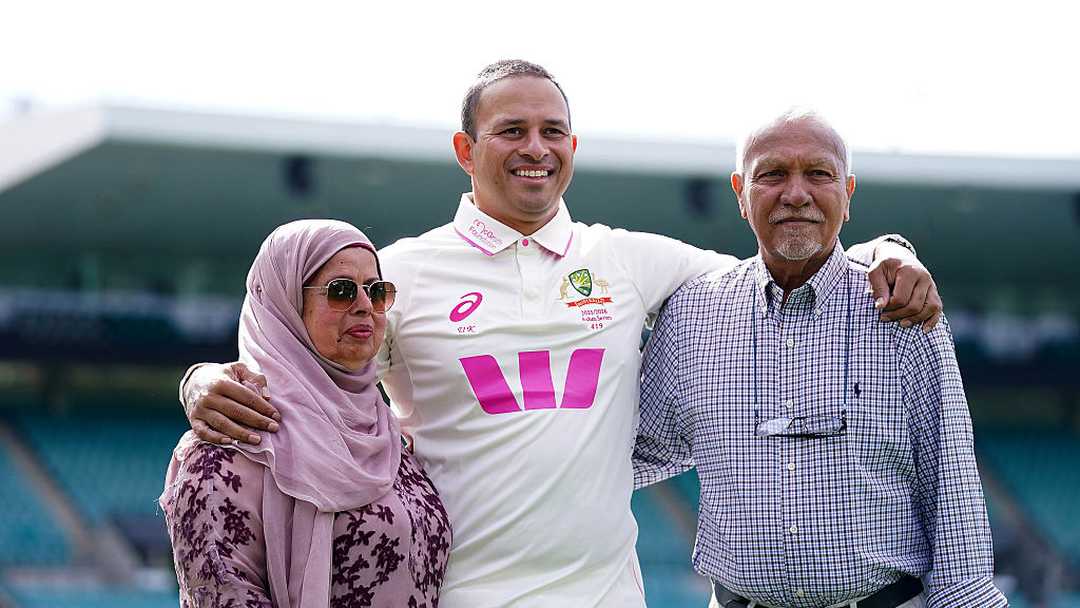

Lived experiences I’ve dealt with as an adult for eight summers. Lived experiences Uzzy has faced his whole life as the prominent brown person in a white-dominated field. I arrived at 32 as a relatively known cricket journalist who’d seen a lot. Uzzy grew up in Sydney’s western suburbs after moving from Pakistan at five—called a "curry muncher," rarely able to voice how excluded he felt.

He’s not playing the race card. He’s not playing victim. He’s telling you how it felt. How it feels. So am I. All we seek is empathy and respect.