Vaibhav Suryavanshi and the long way to Patna

Whenever entries opened for the Sukhdeo Narain Inter-School Tournament in Patna, a young man would cycle nearly 90 kilometres from Samastipur just to collect the form. In Bihar, where ambition often outruns resources, those journeys, season after season, stayed with people.

Manish Ojha, a Ranji Trophy cricketer turned coach, knew the story only in passing, until one day the cyclist appeared at his door. He hadn't come for himself. He had come for his eight-year-old son, Vaibhav Suryavanshi.

By then, Sanjeev Suryavanshi's sacrifices were already known. Loans had piled up and farmland had been sold to fund his son's training. Less visible were the routines: days that began at 4am, journeys from Samastipur to Patna with his wife and son, often with three or four boys in tow who would take turns bowling in the academy nets. Tiffin boxes packed not just for Vaibhav, but for everyone who travelled.

Once at Ojha's academy, then located in a small space in Anisabad, Sanjeev would settle in for the day. Watching. Waiting. Saying little. If one bowler tired, another stepped in. Vaibhav kept batting. 500 balls. Sometimes more.

The routine repeated every alternate day. On days they didn't travel to Patna, Vaibhav batted on the terrace at home in Samastipur. Sanjeev spent those mornings calling around, arranging for bowlers willing to make the trip the next day.

As a coach, Ojha was cautious in the early months. "Bilkul hi baccha thha. Agar zyada tez daal dete, lag sakta tha [He was a child. If we bowled too fast, he could get hurt]," Ojha recalls. So for a long time, he stuck to underarm full tosses, synthetic balls fed gently from the hand. "At that age," he adds, "potential is very difficult to judge."

Then, one day, something changed.

Six or eight months into training, Ojha decided to use the Robo Arm, more out of curiosity than anything else. The speed was set at around 130-135 kilometres per hour. Until then, most of what Vaibhav had faced followed a predictable arc. Not this. "Achaanak usne speed adjust kar liya [All of a sudden, he adjusted to the speed]," Ojha says. "It was a big surprise, even for me."

The surprises became more frequent.

At the newer and bigger academy ground in Sampatchak, on the outskirts of Patna, Ojha watched Vaibhav bat alongside a state Under-19 player on a worn-out surface. The Under-19 player struggled, Vaibhav did not. "On that pitch, he wasn't beaten even once," Ojha says.

Not long after, Ojha asked Vaibhav to skip a practice session and play a match at the academy instead. The opposition included pacers and spinners who had played Under-19 and Under-23 state cricket. Vaibhav, meanwhile, hadn't even played district cricket. He made 118. Ojha remembers the exact score, and every shot. "None of the sixes was under 80-85 metres," he says.

Ojha watched the innings seated beside Sanjeev. When it ended, he turned to him and said, "Your son is ready for big cricket." It was the moment his doubts settled.

The pace of Vaibhav's progress pleased Ojha but it also unsettled him. In practice, Vaibhav hit freely, sometimes too freely. "Doubt hota tha [I had doubts]," Ojha says. "Practice is one thing, but matches are a totally different beast. I wanted Vaibhav to learn how to bat long, how to survive without relying entirely on boundaries."

So he began to complicate things.

On cement wickets, Ojha would pour water before sessions, making the synthetic ball skid and come on quicker. At times, two pacers would bowl with new balls. On other days, sand and small pebbles were scattered to simulate a wearing wicket with unpredictable turn. These weren't drills designed for comfort, but to inculcate patience.

But Vaibhav kept hitting.

The shots weren't wild. They were measured, they were controlled. Even when Ojha tried to pull him back, the response remained the same.

After one such session, meant specifically to make him bat time, Ojha finally stopped the drill. He asked Vaibhav why he was still attacking even when he had been told not to. "Jis ball ko chhakka maar sakte hain, single double kyun lein? [Why take a single or a double off a ball you can hit for six?]" Vaibhav said.

After that point, Ojha stepped back. "Then I stopped asking him to control his aggression."

That response from Vaibhav had stayed with him. Not just for what it revealed about his clarity and aggressive mindset, but also because of how rarely he spoke at all.

Coaching, Ojha says, often involves constant intervention. "Bachchon ko rokna-tokna padta hai [You have to stop them, interrupt them]. You have to scold, sometimes you even have to pull their ears but I had to do none of that with Vaibhav."

With Vaibhav, those interruptions were rarely needed. "Whatever I said, he followed" Ojha says. "Explain it once, that's enough."

Vaibhav didn't speak much, didn't ask many questions and didn't need reassurance. For a long time, Ojha says, people at the academy barely heard his voice. Except when he was looking for a way out of fielding or fitness drills.

"Pet mein dard ho raha hai (My stomach is hurting)," he would say, Ojha remembers with a laugh. "I'd tell him to do a bit of batting and the stomach ache would disappear."

On the field, though, there was no such evasiveness. The instructions went in quietly and stayed there. And as the years passed and the cricket began to speak for him, Vaibhav slowly began to do so as well.

"Aaj hum uski awaaz samajhne lage hain [Now we've begun to understand his voice]," Ojha says.

The work itself with Vaibhav remained traditional. Ojha was clear about what he could and could not offer. "People come to me and say they want their child to play the IPL. I've played Ranji, I tell them I can only train them for that."

The sessions with Vaibhav reflected that clarity. Ojha spent hours on basics. Drills for the cut, the upper cut, the pull. Stepping out and driving. Head position. Footwork. More footwork so that he doesn't become predictable.

"Woh ABCD ke saath aaya tha [He came to me having learnt the bare basics]," Ojha says. "Ab shabdo se grammar kaise banate hain, sentence kaise banate hain, wo humko usse seekhana thha [Now how do you make grammar, how do you form sentences, all that I had to teach him]."

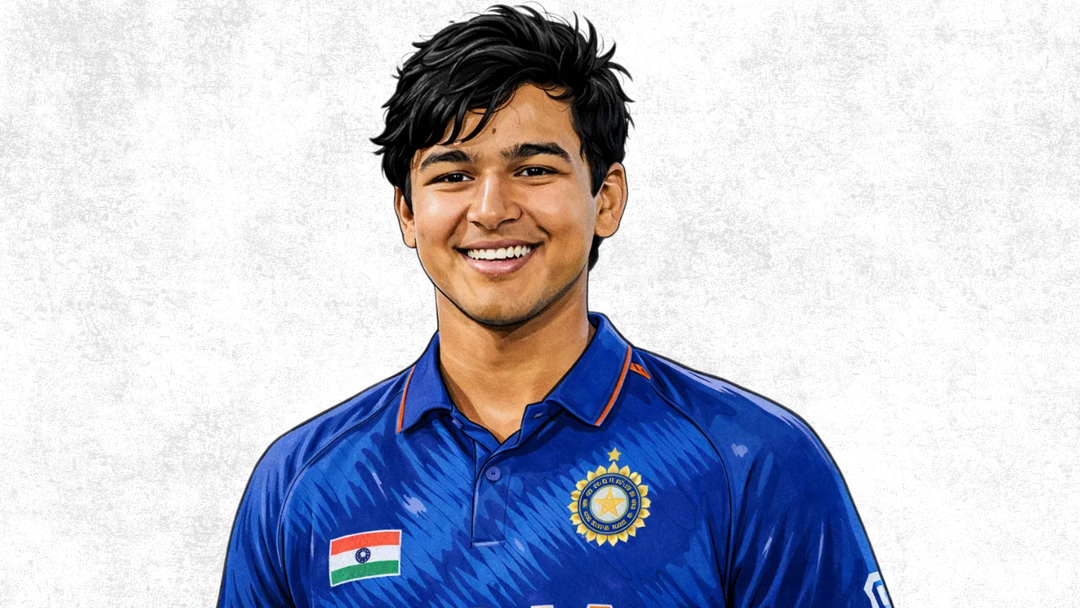

The milestones followed. A century on debut in a youth Test against Australia. An IPL contract at fourteen. A first-ball six. Then 101 off 38 against Gujarat Titans.

After the IPL hundred, a Rajasthan Royals media manager asked Vaibhav who he would call first.

"Papa ko hi karunga," he said in the video shared by the franchise, his tone rhetorical, as if the answer wasn't obvious enough.

When the call connected, his voice softened, instinctively returning to a place far removed from the noise of the stadiums he now occupies. "Papa parnaam."

Not pranam, but parnaam. The way it is said in Bihar, the vowel stretched, the sounds reshuffled.

It was a small moment, held together by his small word. In it were his father, his home state of Bihar and all the journeys that once led him, again and again, to its capital, Patna.